The Adverb Is Not Your Friend: Stephen King on Simplicity of Style

by Maria Popova

“I believe the road to hell is paved with adverbs, and I will shout it from the rooftops.”

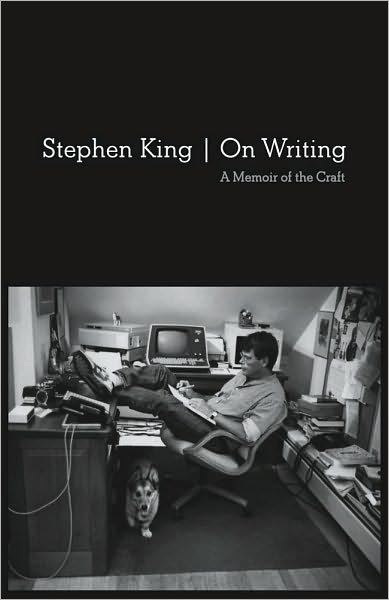

“Employ a simple and straightforward style,” Mark Twain instructed in the 18th of his 18 famous literary admonitions. And what greater enemy of simplicity and straightforwardness than the adverb? Or so argues Stephen King in On Writing: A Memoir on the Craft (public library), one of 9 essential books to help you write better.

“Employ a simple and straightforward style,” Mark Twain instructed in the 18th of his 18 famous literary admonitions. And what greater enemy of simplicity and straightforwardness than the adverb? Or so argues Stephen King in On Writing: A Memoir on the Craft (public library), one of 9 essential books to help you write better.

Though he may have used a handful of well-placed adverbs in his recent eloquent case for gun control, King embarks upon a forceful crusade against this malignant part of speech:

The adverb is not your friend.Adverbs … are words that modify verbs, adjectives, or other adverbs. They’re the ones that usually end in -ly. Adverbs, like the passive voice, seem to have been created with the timid writer in mind. … With adverbs, the writer usually tells us he or she is afraid he/she isn’t expressing himself/herself clearly, that he or she is not getting the point or the picture across.Consider the sentence He closed the door firmly. It’s by no means a terrible sentence (at least it’s got an active verb going for it), but ask yourself if firmly really has to be there. You can argue that it expresses a degree of difference between He closed the door and He slammed the door, and you’ll get no argument from me … but what about context? What about all the enlightening (not to say emotionally moving) prose which came before He closed the door firmly? Shouldn’t this tell us how he closed the door? And if the foregoing prose does tell us, isn’t firmly an extra word? Isn’t it redundant?Someone out there is now accusing me of being tiresome and anal-retentive. I deny it. I believe the road to hell is paved with adverbs, and I will shout it from the rooftops. To put it another way, they’re like dandelions. If you have one on your lawn, it looks pretty and unique. If you fail to root it out, however, you find five the next day . . . fifty the day after that . . . and then, my brothers and sisters, your lawn is totally, completely, and profligately covered with dandelions. By then you see them for the weeds they really are, but by then it’s — GASP!! — too late.I can be a good sport about adverbs, though. Yes I can. With one exception: dialogue attribution. I insist that you use the adverb in dialogue attribution only in the rarest and most special of occasions . . . and not even then, if you can avoid it. Just to make sure we all know what we’re talking about, examine these three sentences:‘Put it down!’ she shouted.

‘Give it back,’ he pleaded, ‘it’s mine.’

‘Don’t be such a fool, Jekyll,’ Utterson said.In these sentences, shouted, pleaded, and said are verbs of dialogue attribution. Now look at these dubious revisions:‘Put it down! she shouted menacingly.

‘Give it back,’ he pleaded abjectly, ‘it’s mine.’

‘Don’t be such a fool, Jekyll,’ Utterson said contemptuously.The three latter sentences are all weaker than the three former ones, and most readers will see why immediately.

King uses the admonition against adverbs as a springboard for a wider lens on good and bad writing, exploring the interplay of fear, timidity, and affectation:

I’m convinced that fear is at the root of most bad writing. If one is writing for one’s own pleasure, that fear may be mild — timidity is the word I’ve used here. If, however, one is working under deadline — a school paper, a newspaper article, the SAT writing sample — that fear may be intense. Dumbo got airborne with the help of a magic feather; you may feel the urge to grasp a passive verb or one of those nasty adverbs for the same reason. Just remember before you do that Dumbo didn’t need the feather; the magic was in him.[…]Good writing is often about letting go of fear and affectation. Affectation itself, beginning with the need to define some sorts of writing as ‘good’ and other sorts as ‘bad,’ is fearful behavior.

This latter part, touching on the contrast between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, illustrates the critical difference between working for prestige and working for purpose.

Complement On Writing with more famous wisdom on the craft from Kurt Vonnegut, Susan Sontag, Henry Miller, Jack Kerouac, F. Scott Fitzgerald, H. P. Lovecraft, Zadie Smith, John Steinbeck, Margaret Atwood, Neil Gaiman, Mary Karr, Isabel Allende, and Susan Orlean.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.